There Stand Empires

Rules and Guide to Play

"Between a battle lost and a battle won, there stand empires."

Napoleon Bonaparte

There Stand Empires is a computer-assisted system for miniatures wargames of the Napoleonic Wars at the grand tactical level. Using the brigade as the basic unit of maneuver, it allows entire battles to be fought on a regular wargames table with a reasonable number of figures. Designed for 15mm scales and smaller, it uses a popular basing system for the period. (It can be played in 25mm or larger scales by doubling all base sizes, measurements, and distances.)

Players will find that There Stand Empires places them firmly in the role of corps and army commanders: anything which is the purview of lower-level commanders is abstracted, and calculated using a model of probabilities within the computer. This extends even to such aspects of battle as formations: these would be dictated by brigade commanders as they fulfilled their orders, in line with national doctrine. (Corps commanders do not order brigades to form column!) In this game, formations are more an indicator of actions being currently taken in response to orders - and to the attendant vulnerabilities of troops - than they are a literal depiction of the unit in question. Similarly, the on-going skirmishing and unimportant combats assumed to be taking place are completely ignored. What is represented are the outcomes of decisive actions. This produces a game which may seem strange to some miniatures gamers who are used to simultaneously commanding at the level of army, corps. division, and brigade. It also has the effect of speeding play considerably. The computer allows more complex modifiers and calculations than paper-and-dice systems however, so that a "fast-play" game doesn't sacrifice realism for speed.

The system is designed to run on any computer or device which has a javascript-enabled web browser. Multiple versions of the software can be run at the same time in a single game. As a computer-assisted miniatures game, There Stand Empires uses a minimalist design. It does not duplicate any of the information which is represented on the tabletop, but functions strictly as a "wargames calculator," replacing the dice-rolling and chart look-ups of other systems. It requires no computer set-up: players must only provide figures, terrain, rulers/tape measures (in inches), and a smart-phone, tablet, or computer which can run the game.

There Stand Empires is based on the earlier system La Guerre à Outrance, but is considerably modified from that system, to reflect period differences. Notably, firepower is considerably reduced (especially artillery) and the game allows for a greater breadth of unit sizes and actions (e.g., the addition of squares). The feel of play is similar, however, allowing for large battles to be decided quickly, but without losing too much realism in terms of outcomes.

The Napoleonic period is a favorite with miniatures wargamers for a reason: the armies are colorful, the range of battles is broad, and it epitomizes the concept of "horse & musket" wargaming for many. There Stand Empires provides a novel way to refight these battles in all of their glory, but without bogging down in the minutiae of tactical detail or endless die-rolls and modifier look-ups.

I would like to thank the Monadnock Historical Wargaming Association for their input and patience over the years as we have playtested and improved this system. I couldn't ask for a better group of guys to game with!

This game is intended for use with smaller-scale miniatures, such as 15mm, 10mm, or 6mm. The number of figures per base is unimportant in this game, as casualties are tracked by the removal of entire bases. Players should put as many figures per base as needed to achieve the desired aesthetic effect. For use with larger-scale miniatures, it may be desireable to double all base sizes and distances in the game, but this will also reduce the effective playing space.

The basic troop types in this game are infantry, artillery, cavalry, and transport. Basic units are at the brigade level, rather than at the lower levels of the regiment or battalion like some other systems. Each type of unit will be described here, along with the typical organization of forces. (Note that in some armies, large regiments functioned like brigades - we use the term "brigade" to mean a tactical grouping of battalions broadly.)

Infantry Units: The basic infantry unit in the game is an infantry brigade. Infantry brigades were historically composed of a number of battalions which might or might not belong to the same regiments (regiments were often administrative organisations, rather than tactical ones). Typically, a portion of the brigade will operate as skirmishers, whether this is a dedicated unit within the brigade (made up of light infantry) or whether it is a set of light companies from the constituent battalions. Brigades are assumed to consist of a majority of formed infantry units, with a skirmishing screen of light infantry (or similar). This is represented on the tabletop by a unit made up of from 2 to 10 bases. Each base will have a 1-inch frontage, and a depth of from .75 to 1 inch. Battalions in the field are assumed to represent around 500-1000 men on average (although this can be adjusted to suit the battle being depicted), each typically being represented by a single base, although very large battalions may require 2 bases, and sometimes very small ones will be combined into a single base. Note that artillery batteries associated with the brigade are fielded as separate units.

For the French, a typical infantry division will consist of two or three brigades, each of two to four regiments providing two to four battalions. Six- and 8-base brigades are probably typical. To this formation would be attached a battery of artillery for each brigade (see below). This was, of course, highly variable.

There are four quality levels: "Elite," "Veteran," "Average," and "Poor." The Elite rating is reserved for the very best troops, such as the French Old Guard (the Young and Middle Guards would be rated Veteran in the later stages of the Napoleonic period). Veterans are well-drilled troops with experienced officers. Average troops are well-drilled and equipped troops, with competent leadership. Poor troops are conscripts and poorly-equipped troops, or those whose officer corps is significantly lacking in practical skill.

Dedicated light infantry formations such as the British "Light Division" are generally rated one class better than regular troops, as operating in skirmish formation required a higher level of training, leadership, and discipline than working in close order. The historical performance of troops should be the guide here: Russian jagers, for example, might or might not be considered better troops than the line formations, depending on which part of the Napoleonic era is being depicted. Austrian grenadier brigades would typically be rated as either Veteran or Elite - one class better than the line formations in the same army. (Be aware that "guard" infantry is not necessarily better than the line - sometimes it is merely a fancy title!)

Cavalry Units: There are two types of cavalry in this game: "light" cavalry and "heavy" cavalry. The first category rode lighter horses and often was employed in scouting and similar functions. This includes hussars, chasseurs a cheval, light dragoons, and similar types. Cuirassiers, carabiniers, and similar types of cavalry are considered "heavy", being used in close order on the battlefield. They rode larger horses, and were generally not employed in the same type of campaign duties as the light cavalry. Some categories are harder to classify, specifically dragoons and cheveaux legere, as these categories were used in different ways by different countries at different times. Dragoons should generally be considered "heavy" cavalry if they are equipped with straight swords (as opposed to sabres) and were well-mounted, or if they are operating in theatres where there was a lack of heavier types, and they would be pressed into this role (French dragoons in the Peninsula, for example). Chevaux legere are a special case, as these were sometimes used as "heavy" cavalry, despite their title. When equipped with straight swords, this is an indication that they would be used in the role of battle cavalry rather than as lighter scouts. In cases where dragoons, chevaux legere, or uhlans/lancers are brigaded with heavier cavalry, then the entire brigade should be classed as "heavy" for game purposes. Note that heavy cavalry maneuvers more slowly, but has an advantage in combat.

Cavalry is assigned a quality in the same fashion as infantry: "Elite," "Veteran," "Average," and "Poor." As for infantry, Elite formations would be very rare. A primary determinant of quality rating in this game will be the quality of the horses available: in 1813, for example, Napoleon was hard-pressed to find good mounts for his cavalry after his mis-adventure in Russia, so cavalry which might earlier have been rated Veteran would become Average, etc. Austrian hussars, on the other hand, were often very well-mounted and will often be awarded a Veteran rating as a result. (This is in addition to considerations of training and leadership, of course.)

Cavalry bases should be 1 inch wide and .75 to 1.25 inches deep. Each base will represent 2 or 3 squadrons, numbering 100 to 200 men per squadron. This was highly variable, so a consistent representation based on the strength of brigades should be used. Cavalry units are organised in brigades, typically of from 2 to 8 bases. Attached artillery batteries are represented separately.

Artillery Units: Each artillery base represents a single battery of from 6 to 8 guns. Russian 12-gun batteries should be represented with two bases. There are three types of artillery in the game: "heavy foot" batteries, "light foot" batteries, and "horse batteries". Although howitzers were often mixed in with other types of guns in a single battery, units are classed according to their majority type for game purposes. Heavy Foot Artillery is equipped with 8-pounder to 12-pounder guns. Light Foot Artillery is lighter, typically consisting of 6-pounders or 4-poiunders. Horse Artillery is similar to Light Foot Artillery except that it is equipped for faster movement, with gunners mounted, and is trained to perform a more flexible and aggressive role on the battlefield in support of cavalry.

It is typical for a division to have a battery for each of its brigades, and for several batteries of different types to be assigned at the corps level (see below).

Artillery units should be mounted on bases 1 inch wide and 1 to 1.5 inches deep. All artillery units are given the same quality rating in this game, as the technical nature of artillery service tended toward standard levels of competence.

Transport: In some scenarios, non-combat units representing supply transport will be represented, typically as a target for the enemy according to scenario victory conditions. Such units move slowly and do not perform offensive combat actions. They will attempt to defend themselves, as they are assumed to be accompanied by guards of some description. Such units suffer normal combat outcomes, but scenarios may specify that any defeat results in capture, ot other outcomes as required by the scenario. Transport bases should be 1 inch wide and 1-2 inches deep to accomodate the wagon models, or whatever figures are used to represent the transport.

Generals: This game represents army-, corps-, and division-level generals on the tabletop, referred to also as "leaders" for game purposes. Each is represented using one to three mounted or dismounted figures (in 15mm - more for smaller scales) on a circular base which is .75 to 1 inch in diameter (alternately use a 1-inch square base). Each represents a general and his attendant staff. They have no combat function (nor are they subject to attacks) but do have an influence on how well troops execute orders (notably movement, assault, and regrouping actions). Army and corps generals may be mounted on larger bases (1.5 inch and 2 inch, respectively) if desired. Note that army-level generals should only be represented if they took an active command role during an historical battle, which was not always the case.

Markers: Only two types of markers are needed for this game: disorder markers and demoralization markers. These can take any form - counters, small round bases with one or two casualty figures on them (one for disorder, two for demoralization), etc. Optionally, markers may be used to indicate which units have already gone this turn (not critical for smaller games, but generally useful). Small chits are good for this, or small models which will enhance the look of the tabletop but are distinct from disorder and demoralisation markers, such as ammunition crates on small round bases, etc.

Game Scales: Each inch represents about 150 yards, giving us a "rule-of-thumb" 12-inch mile (approximately 1.5 kilometers) for laying out the gaming table. This means that most period battlefields can be depicted on a normal wargames table. Each turn represents an hour of elapsed time. Consequently, combats tend to be decisive in their effects, even though they do not represent continuous combat of an hours' duration in most cases, but a shorter period of intense conflict surrounded by other related activities.

Gamers who are used to more tactically oriented rules will find it strange that units cannot combine activities as freely as they might wish. Remember that only the most significant activities are reflected here. Individual volleys, battalion evolutions, and skirmisher interactions are simply not explicitly represented in this game, being deemed below the notice of corps commanders. They are assumed to be on-going. More significant operations, however, take time. Deploying artillery and producing enough fire to have a noticeable impact took time, and between sending out orders and deploying to perform any type of battlefield maneuver likewise could take longer than what we expect from watching movies and from tactical wargames. Gamers want to see these things happen instantly, but the historical record demands otherwise. This game system is calibrated to reflect the historical pace of entire battles, not immediate tactical actions, unlike many other rules sets.

The French take on Prussians and Russians in 1813.

The game app acts as a point of reference for several different activities during play. The game itself is run like most other tabletop miniatures wargames using a turn sequence, as described in the next section. The app does not drive the turn sequence, or guide players through it - it is a tool used to perform certain functions at specific points during play. These include determining initiative at the start of the turn, resolving most movement actions, resolving combat actions, checking to see if isolated generals are killed or captured, and determining when an army breaks. Each of these is described below.

Determining Initiative: For any game, one side is designated the "Attacker" and the other the "Defender". At the start of each new turn, the "Initiative" button is clicked, giving the choice of who goes first to the indicated side. Initiative will alternate between sides for the rest of the turn (See below).

Resolving Movement: Several of the actions listed below involve moving troops and/or changing formations, some of which may be combined with other actions. These are performed by selecting the type of acting unit, the type of action, filling in other needed fields (as decribed for each action, below), and clicking on the "Result" button. The app may ask for further input: in all cases, "OK" means "yes" and "Cancel" means "no" when responding to these prompts. The result of a movement action always includes a possibility that orders will be lost or delayed, so every movement action must use the app to determine if it succeeds, even though movement rates are predictable.

Resolving Combat: Several of the actions listed below involve firing on or assaulting enemy units. These are performed by selecting the type of acting unit, the type of action, the type of target, and filling in other needed fields (as described for each action, below), and clicking on the "Result" button. The app may ask for further input: in all cases, "OK" means "yes" and "Cancel" means "no" when responding to these prompts. The result of a combat action may include a possibility that orders will be lost or delayed. Every combat action must use the app to determine the outcome.

Killing or Capturing Generals: In the case where an enemy general which is not attached to a unit is overrun by the enemy, there is a possibility that it will be killed or captured. For this action, all that is needed is clicking the "Leader Overrun" button and answering the questions: in all cases, "OK" means "yes" and "Cancel" means "no" when responding to these prompts. The fate of the general in question will be indicated by the app. You must always use the app to perform these checks.

Determining whether an Army Breaks: Once either (or both) side(s) loses 50% of its units, or has them in a Demoralized state, a check must be performed to see if the army breaks. If it breaks, it will flee the field and the game is lost. To perform this check, all that is needed is to click on the "Army Morale" button, and to respond to the questions: in all cases, "OK" means "yes" and "Cancel" means "no" when responding to these prompts. The app will indicate if the army has broken or not.

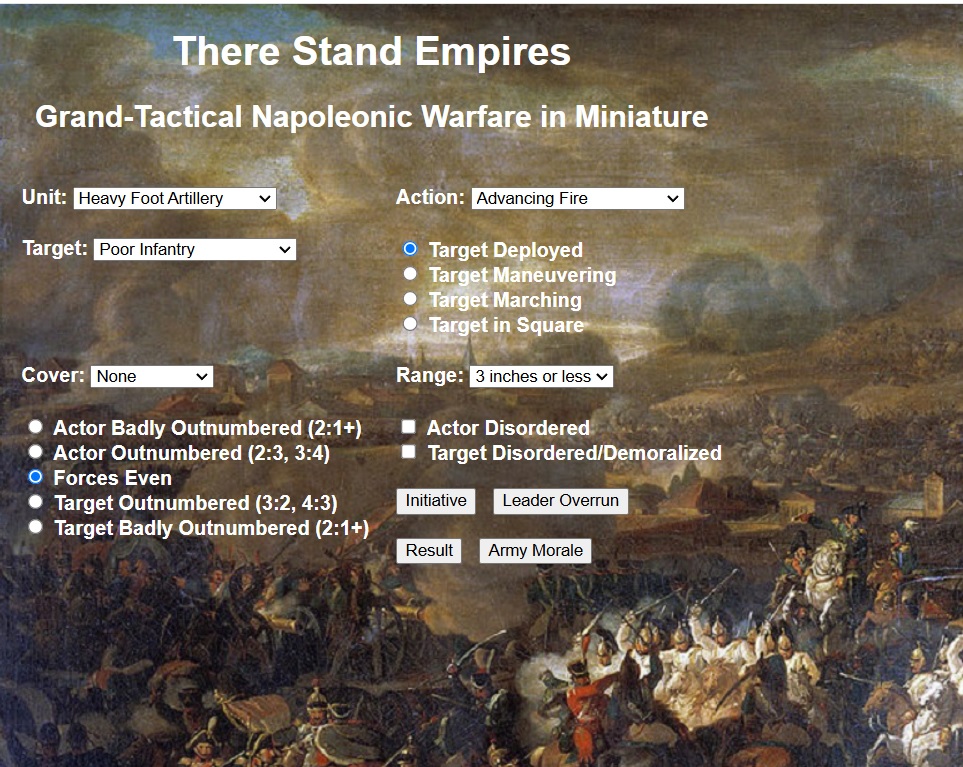

The picture below shows the screen of the game app. The buttons and controls referenced in the text below are all visible here - the game app only has this single screen.

The game is played in a series of turns. Each turn, every unit may make one action. These are organized by initiatives: press the initiative button at the start of each turn and it will pop up a box giving the initiative to either the Attacker or the Defender (these roles are assigned by scenario). That side may choose to take the first initiative, or may force their opponent to do so.

The side with the initiative will select one division in their army, and will perform actions with every unit which is eligible to do so, and will be able to move the divisional general for the force. (Note that corps and army generals may move separately using their own initiatives, instead of a division - see below). The player running that division will select one unit which has not used its action for the turn, and perform any legal action. This process is repeated until all units in the division have performed an action. The opposing side now takes the initiative, and perform the same activities for one of their divisions or corps or army generals. (Once one side acts with all units and leaders, the other side automatically gets the initiative until all units have gone.) Players must use their initiative, although they may always select which division/general will act on it from among those who have not used their action for the turn. Players may wish to mark which units have acted during the course of the turn to make it clear which units have yet to go.

Once all divisions and generals have used their actions, army morale should be checked to see if either army breaks (or both of them). The next turn then begins by determining which side has initiative, and the sequence is repeated.

There are some alternative ways to handle initiative. For those who like a more chaotic game, initiative can be determined randomly using the "Initiative" button for every division, so that one side may move more than once in a row. For smaller games, players may wish to move all generals (including divisional generals) independently, and to use an initiative to act with only a single unit or general, instead of an entire division. (For larger games, this tends to slow play too much, and make it difficult to coordinate attacks and so on.) Such alternatives should be identified by scenario if used.

There are several actions available to players, not all of which require the use of the game app:

Hold/Rest/Stand: Any unit or general may choose to do nothing for a turn as its action. This does not require the use of the program interface. (Once a unit has chosen to do this action, however, it may not "change its mind" later! It is considered to have acted for the turn.)

Move General: A general may move up to 28 inches base movement, in any direction or combination of directions, subject to normal movement rules (as cavalry). This does not require the use of the program interface. Note that general's current position during the turn is the one used to determine whether they influence actions made to nearby units - they may influence a unit, then move to another, and influence it. They will influence all units nearby - there is no limit to this number. They may only move once during the initiative, however, and may not stop along the way to influence units before moving on.

Deploy/Maneuver in Line: This changes a unit into a linear formation, taking advantage of available cover, etc., screened by skirmishers and supported by columns in reserve. Deployed cavalry units will be spread out in whatever formation is best suited to their protection, in available folds in the terrain, well-spaced out, etc. This is primarily a defensive measure, to reduce their vulnerability to fire. A deployed formation is one base deep, with all bases sharing a facing, side-by-side, but they may adjust the front slightly to follow terrain features such as walls. Guns are unlimbered and ready to fire. (See the rules below regarding Deployed formations.) It is legal to re-deploy a unit which has already been deployed to reposition it, which is termed a "maneuver in line". All units other than generals (who are not technically units, and have no formation) may deploy. The program interface must always be used, because there is a chance that transmission of orders may fail or be delayed. Only the Actor and Action fields need to be used for this action. Note that some units may Deploy or Maneuver in Line and still perform Advancing Fire in the same initiative.

Maneuver in Column: This represents the typical movement of a unit on the battlefield. For infantry and cavalry, it represents a set of smaller-unit columns, screened by skirmishers. For artillery, it is limbered movement in expectation of imminent action. Generals may not perform this action (they are not technically units). Fire from a maneuver formation is less than that of a deployed formation. It is represented on the tabletop with a formation generally at least two bases deep, and at least two bases wide. All bases are placed side-by-side, sharing a facing. (See the rules below regarding Maneuver Column formations.) All units other than generals may maneuver. The program interface must always be used, because there is a chance that transmission of orders may fail or be delayed. Only the Actor and Action fields need to be used for this action. Note that a Moving Fire may be made in combination with this action if movement is restricted by half. This may be made only after the unit moves.

Form Square: This order is used by infantry to assume battalion or regimental squares on the command of their brigadier - it does not represent the forming of emergency squares as a result of an attack by cavalry, which is done automatically when required (or not!). The infantry unit will assume a square formation. (See the rules below regarding Square formations.) Any artillery units in contact with the infantry will remain in contact with the square, and are assumed to be protected as well. This action requires that the Actor and Action fields are filled out.

Deployed Fire: When an infantry or artillery unit is deployed, it may fire. This action cannot be performed by units in a Maneuver Column, Square, or March Column formation. Targets must be within range and arc of fire (see Firing, below). Deployed fire may not involve any facing changes. The program interface must always be used to calculate the effects of fire. The Actor, Action, Target, Target Formation, Cover, Range, and Disordered/Outnumbered fields are all used for this action.

Advancing Fire: When an infantry or artillery unit is in Maneuver Column or Square formation, or in the turn that it assumes a Deployed formation, it may often conduct fire. This action cannot be performed by marching units. It represents fire by those units at the front of a formation, and - in the case of artillery - the rapid unlimbering and firing of batteries with the ammunition supply immediately available. Targets must be within range and arc of fire (see Firing, below). Advancing fire may involve facing changes or other movement when combined with other movement actions, but the movement action should be taken first. The program interface must always be used to calculate the effects of fire. The Actor, Action, Target, Target Formation, Cover, Range, Disordered/Demoralized and Outnumbered fields are all used for this action.

Assault: This represents a charge into close combat. It may only be performed by infantry or cavalry units starting the action in Maneuver Column formation (see exceptions for "linear" units, below). The target of an assault must be visible to the assaulting unit - facing changes and wheels are allowed before an assault is conducted (see Assaults, below). The target of an assault is considered to have used their action for the turn, if they have not already done so, unless the assault is stopped by fire before reaching it's target. The program interface must always be used to calculate the effects of an assault. The Actor, Action, Target, Target Formation, Cover, and Disordered/Outnumbered fields are all used for this action, but the Range field is not.

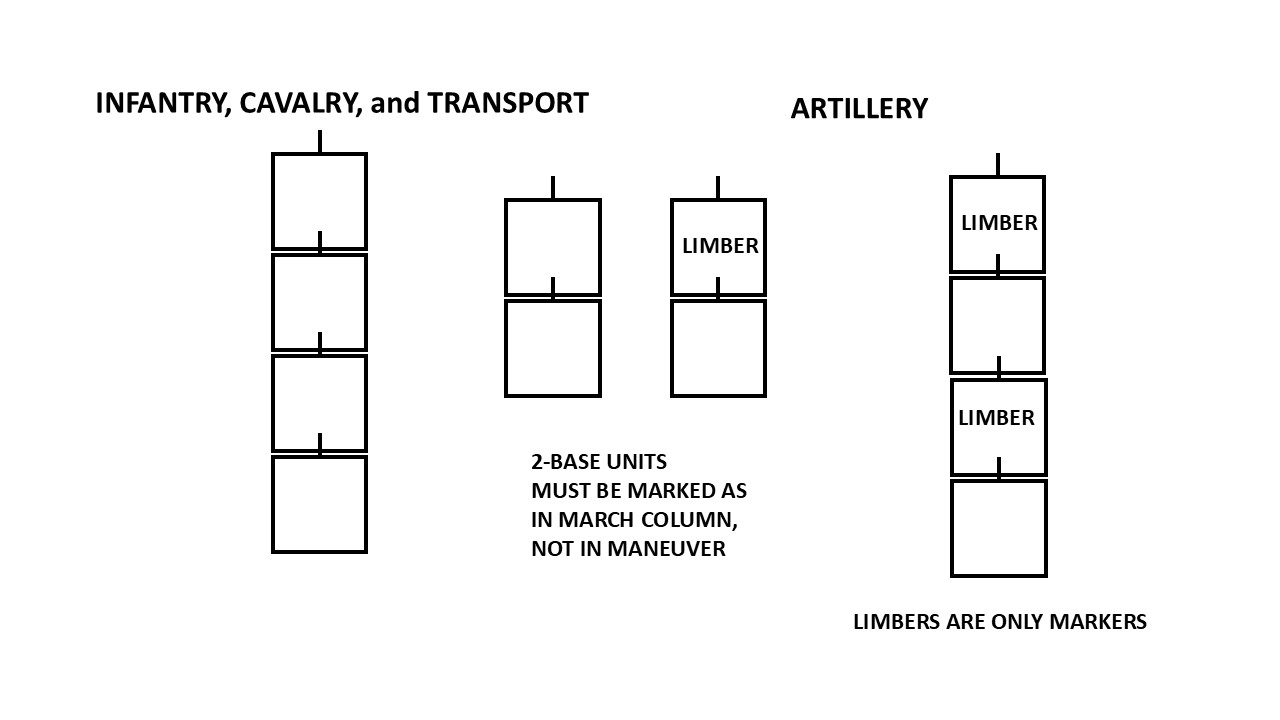

March: This represents the movement of a unit on the march, without the expectation of enemy contact. The unit will assume a March Column formation, one base wide. (See the rules below regarding March Column formations.) March columns get a benefit from marching on roads (see Movement, below). Fire from a march formation is not allowed. The program interface must always be used, because there is a chance that transmission of orders may fail or be delayed. Only the Actor and Action fields need to be used for this action.

Route March: This is a march action made in those scenarios where a unit marches onto the tabletop. They are assumed to have already successfully received their march orders, and be executing a long march to the field. Units performing this action will assume a March Column formation. Base moves are: Elite and Veteran Infantry, 14 inches; Average Infantry, 12 inches; Poor Infantry, 10 inches; Elite and Veteran Light Cavalry, 28 inches; Average Light Cavalry, 24 inches; Poor Light Cavalry 20 inches; Elite and Veteran Heavy Cavalry, 24 inches; Average Heavy Cavalry, 20 inches; Poor Heavy Cavalry, 18 inches; Heavy and Light Foot Artillery, 12 inches; Horse Artillery 20 inches; and Transport, 12 inches. The route march ends as soon as the unit performs any other action. Scenarios should specify where the marching unit is going on the tabletop (or what choices the players have to determine this). This action does not use the program interface.

Regroup: This represents the reorganization and rallying of troops. The regrouping unit must be disordered or demoralized. If successful, it may assume any formation/facing desired (the center-point of the unit should not change, and no part of the uit may come within 1 inch of the enemy). All units (except generals, which are not units per se) may perform this action. The program interface must always be used, because there is a chance that the regrouping action may fail. Only the Actor and Action fields need to be used for this action.

An action is taken using the program interface by selecting the correct values for the necessary fields and clicking the Result button. One or more pop-ups will appear, some requiring answers to simple yes-or-no questions ("OK" is yes and "Cancel" is no). The results of the action will be provided in a pop-up, and changes should be made on the tabletop as indicated. A unit which has been the target of one or more Assault actions during a turn may have used its action for the turn, whether it has yet to perform another action or not (see Assaults, below). This sometimes allows players to deny the enemy actions with key units, but this may demand a costly assault against the odds! Reaction to fire does not use a unit's action for the turn, even if it involves movement.

Note that the only permissible action for a unit which is demoralized is to regroup.

Generals never perform any action by themselves other than to move or to hold - they are not "units" in game terms, but are used only to influence command control via proximity. They do not have formations, and can only be removed from play if "run over" by the enemy (see below).

If a mistake is made in using the program interface (if a needed field is set incorrectly), ignore the results and repeat the action with the correct values. If for any reason the program interface freezes, crashes, or is accidentally closed, simply re-start (re-open) the program interface and continue. No needed information will have been lost. The use of fields not specified in the actions as described above will not affect those actions - the game app will just ignore the settings in unused fields, so this will not require repetition of the action on the app.

Multiple copies of the program interface may be used simultaneously during play. So long as players are in agreement about who is adjudicating what on which copy of the program, there will be no problems. Thus, there is no reason to wait for a single game master to adjudicate everything on one instance of the program. For small games this is not important, but it can help to speed play in larger, multi-player battles.

Wurttembergers advance against the Prussians.

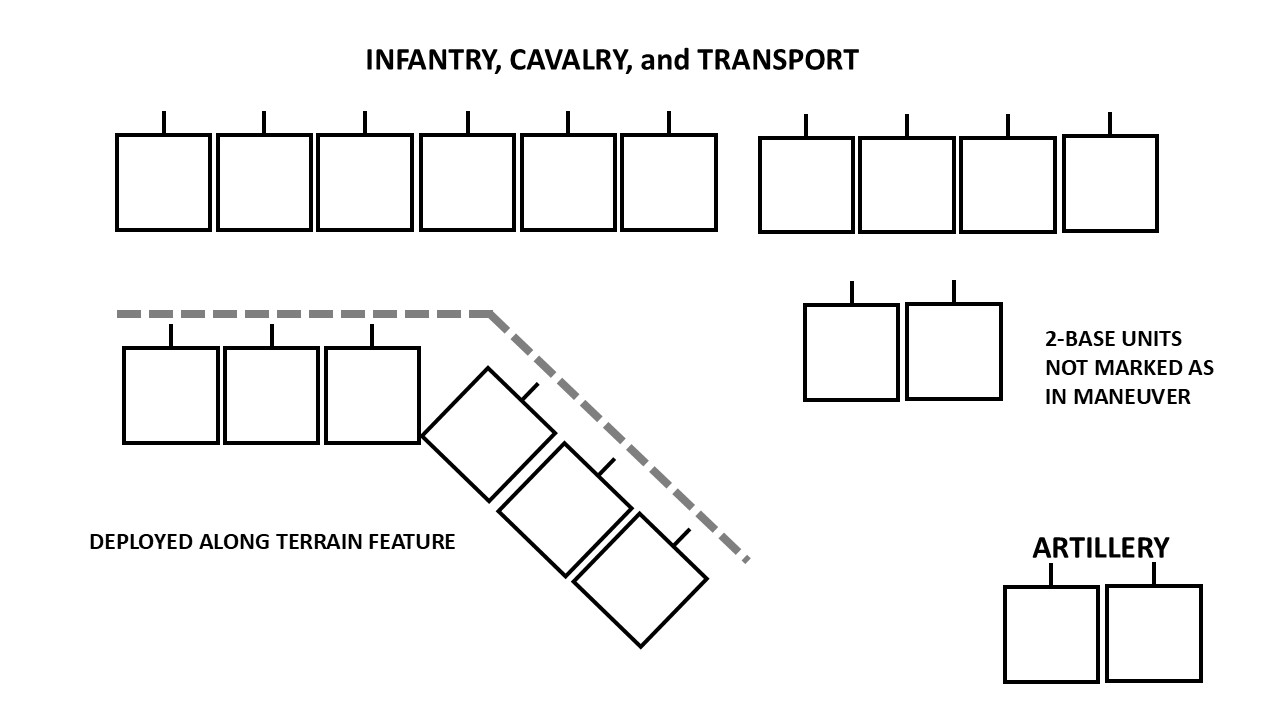

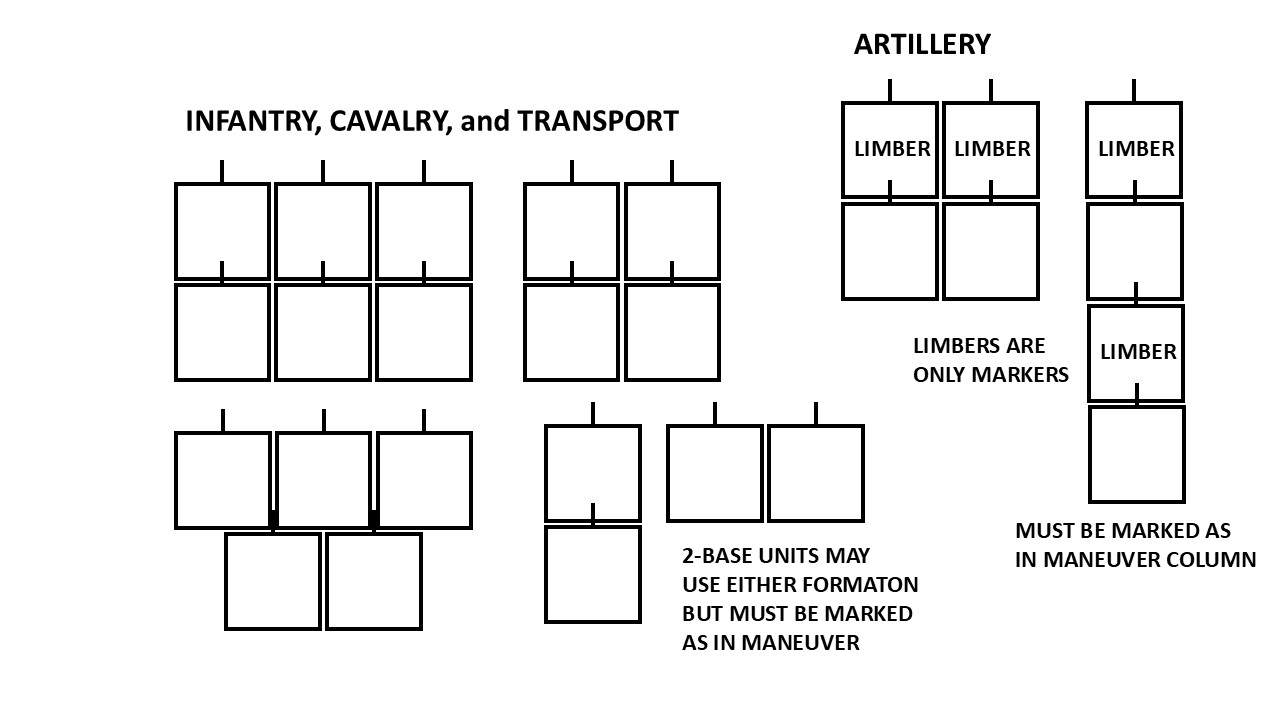

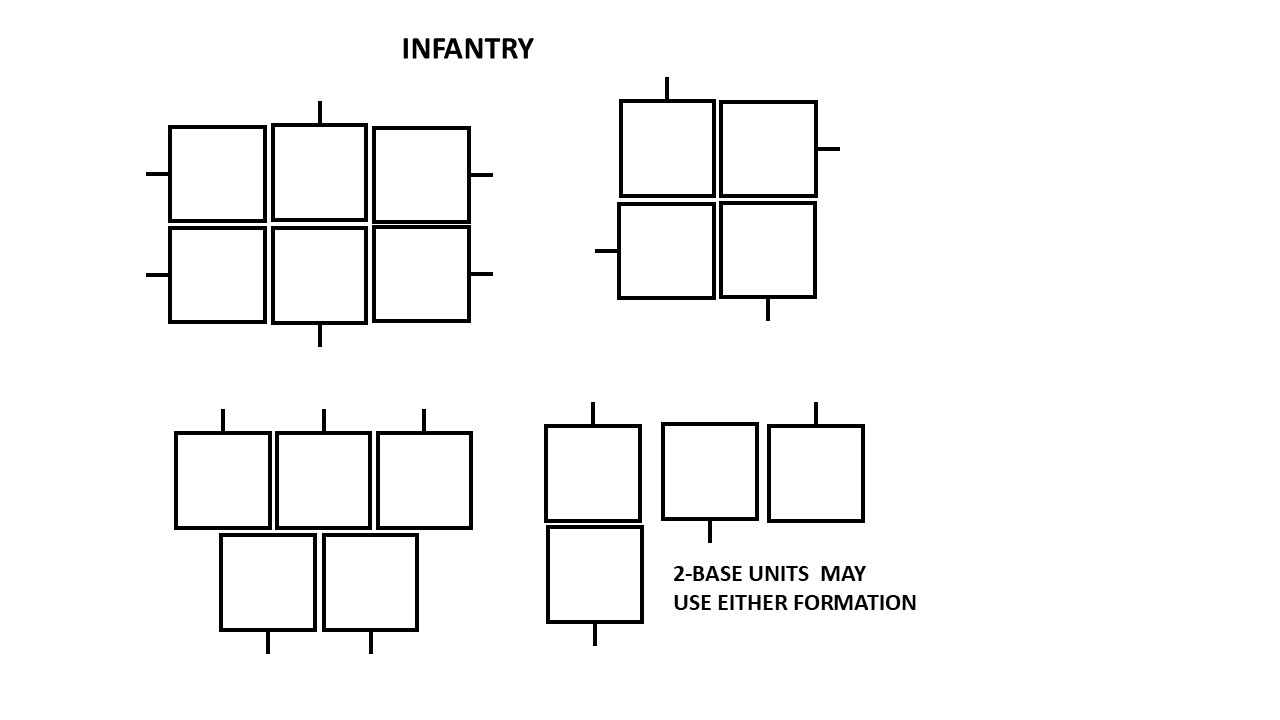

As described above, there are four different formations in this game. All units except for generals will always have a formation (generals have no formation). Typical examples of the formations are shown in the diagrams below, where each square is a base with the facing marked. Note that single-base units also have a formation, but this must be marked as it will not otherwise be known. There is no space left between bases (unless you choose to not use limber markers, in which case these spaces are left empty).

Unlike may other games, formation changes are not something which units use their base movement to perform, at the discretion of players. Such operations are the province of regimental and brigade commanders, not higher-level generals. Instead, formations are an inherent part of the performance of orders, and they happen without movement penalty as soon as the unit executes the order in question. When a unit is told to Maneuver, it goes into Maneuver Column facing in the desired direction before performing the desired movement. Likewise, when ordered to Deploy a unit arranges itself in a linear formation. When ordered to March, it assumes a March Column before executing orders, and so on. This may seem strange to gamers used to other systems, but it is appropriate to the command level and time scales for this system - lower-level formation changes are abstracted because they are performed by the brigadiers. This helps to speed play considerably, and reflects the appropriate vulnerabilities of units as they execute orders.

Note that units which are disordered or demoralized will retain their formation, and simply be marked as disordered or demoralized. Disorder and demoralization do not affect base movement distances.

Deployed Formation: All bases sharing a facing, one base deep, arranged side-by-side. The line thus formed is allowed to bend to accommodate terrain features such as a wall, the edge of a woods, a ridge line, etc. Units assume a deployed formation only by performing a Deploy action. When deploying, a single base from the unit is selected as the reference point, and may shift its center up to 1 inch in any direction. It may change facing as desired. Other units are then deployed around it, in whatever directions the player wishes so long as the resulting formation is legal. It must not bring any base within 1 inch of an enemy unit. Once deployed, a unit may not move except as a Maneuver in Line (which is another Deploy action, moving 1 inch in any direction, essentially). A unit may not make deployed fire without starting the turn in a deployed formation. An Advancing Fire action may be taken by some units after the Deploy is complete.

Maneuver Column (or Advancing) Formation: When a maneuver action is made, the unit will immediately assume the Maneuver Column formation, which is always at least two bases deep, but which may vary in width. Bases should be arranged in even ranks to the extent possible (no rank may have more bases than the front rank, nor more than 1 fewer than any other rank in the formation). All bases share a facing. When assuming a maneuver formation, any desired facing may be used (center-point of the unit does not change). When a maneuver action is taken, first the Maneuver Column formation is assumed and then the move itself is performed. During this movement (both March and Route March actions), the unit may freely turn as it maneuvers in any desired combination of directions, wheeling off the corners of the front base. The movement will end with the unit still in Maneuver Column formation.

There is an exception to the 2-deep rule above when a unit has only 2 bases. Such units may choose to maneuver with their two bases side-by-side in a single rank, but must be marked as being in a Maneuver Column formation whether in one or two ranks. Similarly, artillery may choose to maneuver in a single base-width column, but this needs to be marked to distinguish it from a March Column.

An advancing fire may be made if only half or less of the allowed movement is used, but movement must be performed first in the turn.

March Column Formation: When a march action is made, the unit will immediately assume the March Column formation, which is always only one base wide, with the units bases arranged in a front-to-back fashion. All bases share a facing. March Column formations are formed by selecting a single base to be the front of the column, facing it in the desired direction, and arranging the other bases in the unit behind it. The formation of the column may not bring any bases within 1 inch or less of an enemy unit. The column may bend ("snake") to follow roads or other terrain features being marched along. During this movement, any number of facing changes is permitted - the unit may freely turn by wheeling off the corners of the front base as it marches in any desired combination of directions. The movement will end with the unit still in March Column formation.

Square Formation: When a Square is formed, the bases of the unit are turned outward to all of the different sides of the unit. This represents an equal distribution of troops on all sides of the Square for game purposes, all facing out. In game terms, this does not represent one large square (typically) but a set of battalion or regimental squares for all the component units in the brigade. (While this was fairly rare, there are occasions where brigades were ordered into square by generals anticipating a cavalry attack). One base of the unit is selected and the facing turned as desired, with the other bases in the unit arranged around it. Squares cannot move, and they are only capable of Advancing Fire actions, not Deployed Fire actions.

Notes on Generals: Generals have neither formation nor facing. Because they are neither targets nor actors in any combat situation, this does not affect game play. When they move, they do so as cavalry with a fixed base movement of 28 inches per turn. A general which is "run over" by the enemy will either be killed/captured or moves immediately out of the way (see below).

Any portion of a unit's base movement may be spent in an action involving movement (or none of it) but the base moment as adjusted for terrain may never be exceeded. Movement is made in a forward direction relative to the unit's facing (but you can change facing at the beginning of any action permitting movement). You may always wheel off the front corner of the unit, or rotate around the front edge of the unit's center point, paying for the greatest distance moved by the front corner. Movement is made along a path specified by the moving player, measuring from the starting location of any base in the front of the formation to its ending location, up to the distance determined by a modified base move. Any rough terrain or linear obstacle crossed will adjust base movement: the greatest distance the movement path of any base in the formation spends crossing rough terrain costs twice the movement of crossing open terrain (for infantry or artillery) and four times as much (for cavalry). If I maneuver an infantry unit across 2 inches of open ground, then through 2 inches of woods (rough terrain) it will cost my full 6 inches of base movement (2 inches for open ground, and twice 2 inches for rough). Linear obstacles (hedges, stone walls, etc.) will cost an additional 1/2 inch of movement to cross. Choke-points (bridges, gates through insurmountable walls, etc.) will cost an additional 1/2 inch of movement to cross, unless the unit is in march formation. A maneuvering infantry unit passing over a bridge in open country will move a total of 5 1/2 inches, if it has a 6-inch base movement. Movement inside towns is considered rough for movement purposes unless a unit is in march formation (when it is considered to be road movement). Units in march formation will move 1.5 inches for each inch of base movement when they move along a road/through a town (a 50% movement bonus).

Movement through friendly units is allowed, so long as no part of the moving unit ends its turn "inside" another unit. Enemy units may not be approached closer than 1 inch (their "zone of control") by any part of a moving unit except as part of an assault action (see below).

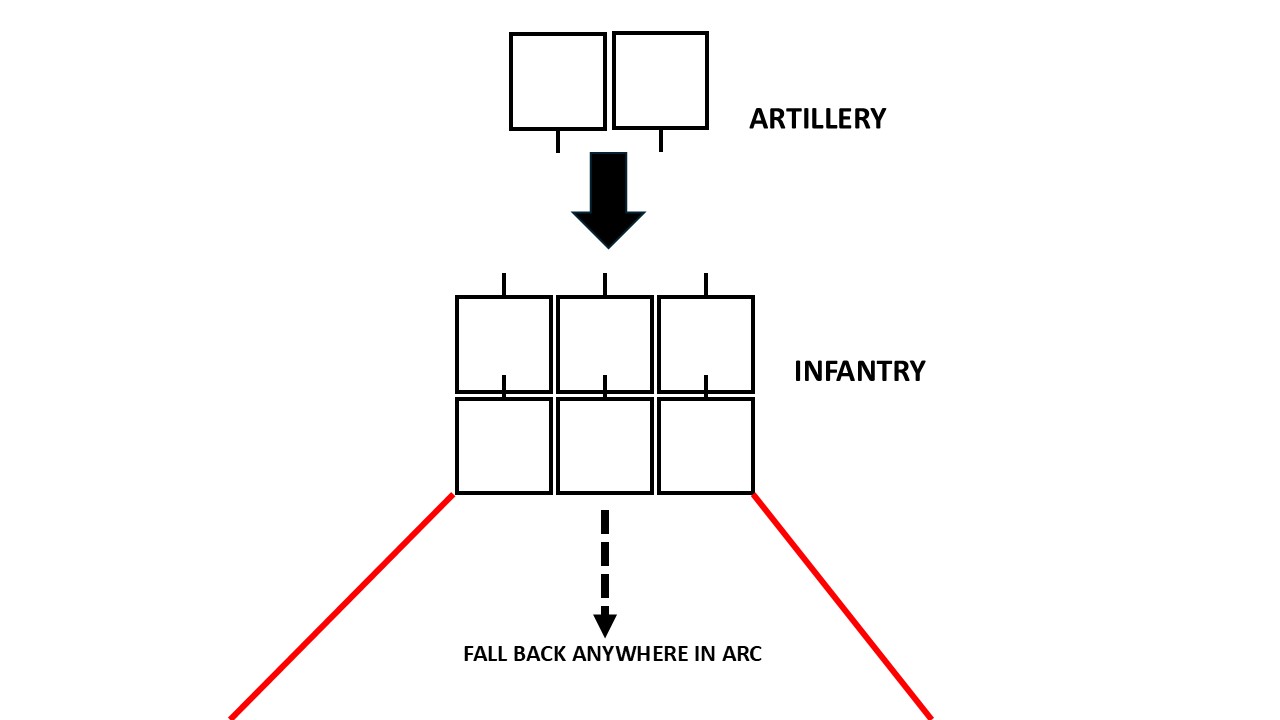

Movement caused by combat results (falling back or pushed back) will abide by all normal movement rules, except that the unit will change its facing at the end of the move, to match the facing it had at the start of it. Such movement must be made away from the source of the combat result (the firing or assaulting unit) in as straight a line as possible and within an arc measured 45 degrees off either side of the rear edge of the affected (moving) unit. The unit being pushed back/falling back will retain its formation and original facing. The diagram below shows an example:

Here, an artillery unit faces an enemy infantry unit. The artillery is deployed. The artillery unit makes a deployed fire action, causing the infantry unit to fall back 6 inches and become demoralized. The infantry unit would move within the arc described by the two red lines, a distance of 6 inches, ending the move without altering its facing or formation, and would be marked as demoralized. It would not turn except as required for its movement to be legal (not within 1 inch of enemy units; not through impassable terrain; not moving so as to end up inside another friendly unit; etc.).

Other non-movement-related aspects of combat effects are addressed in the next section.

Making assault actions also involves movement. This is addressed under Assaults, below.

Note that there is a possibility that orders involving movement (deploy, maneuver, march, and assault actions) will be lost or delayed in transmission. Having a general within 6 inches of the unit receiving the order helps to prevent this from happening (the general is 'on hand' to make sure thing go as planned). When orders are lost, it is still possible to make actions which do not involve movement (fire actions, regroup, etc.).

Unit Status: There are three unit statuses: OK/Normal, Disordered, and Demoralized. All units begin the game with an OK status (also called "fully rallied"), and will retain it until combat effects cause the status to change. Disordered and Demoralized units may make regroup actions. Once successfully regrouped, a unit returns to its OK/Normal status, or may only rise a single level, from Demoralized to Disordered, or from Disordered to OK. Disorder indicates that a unit has suffered some losses, and that it is not responding optimally to command control among and within its units. Demoralization is more severe, indicating further losses and a greater degree of breakdown of discipline within the unit, to the point where it cannot be controlled. A Disordered unit may still function - a Demoralized one is no longer functional, but it has not yet broken (broken units are considered destroyed and are immediately removed from play).

Disordered units may make any legal action (although the Actor Disordered box should be checked if needed when they do so). Disorder makes a unit more vulnerable in combat situations. When firing at or assaulting a Disordered unit, the Target Disordered/Demoralized box should always be checked.

Demoralized units are not permitted to make any action other than regroup. They will fight if assaulted, but will not benefit from coherent defensive fire. (This makes them the ideal candidates for assaults, especially frontal assaults.)

When a unit has become Disordered, it may sometimes receive an additional Disorder from a subsequent enemy combat action or other action. When this happens, the two Disorders add up to a Demoralized status. Once Demoralized, a unit will not become further Disordered or Demoralized (or destroyed/broken) - they will simply remain Demoralized until they successfully regroup or are otherwise removed from play. A unit will only lose bases as the explicit result of an enemy combat action.

In some cases, combat effects will involve involuntary movement (pushed back, thrown back, falling back, etc.). Such movement will be governed by normal movement rules, as described above, with the exception of the final facing of the unit. In cases where such movement may not be legally completed (ie, the affected unit is surrounded by enemy units, or is backed up against impassable terrain) the unit will surrender to the enemy - it is considered destroyed and is removed from play. If a combat effect does not specify movement, then the unit will retain its facing and formation in the position it currently occupies. This movement is made immediately when the combat outcome is reported for the unit.

In some cases, combat effects will specify location. These both occur with assaults: sometimes, an assaulting unit will refuse to enter into combat contact with its target, and will stop 1 inch short of it. The unit will be faced along the line of movement of the assault (see below) and will be positioned, in a maneuver formation, 1 inch from the target unit. In other cases, a unit may be pushed back to its starting position. In this case, the unit will remain in maneuver column, facing along the line of movement of the assault. In both cases, disorder or demoralization will be marked, according to the combat effect. (Note that linear units assaulting in a Deployed formation would use it instead of a Maneuver Column in these situations.)

Losing Bases: Some combat effects involve the loss of one or more bases. This indicates that the unit has sustained severe losses through combat. Lost bases are immediately removed from the affected unit. If at any time a unit loses half or more of the bases with which it started the game, it is considered destroyed and is immediately removed from play. Thus, 2-base (and smaller) units are immediately destroyed if they receive such a combat effect.

For both fire actions and assaults, an acting unit or its target may be considered outnumbered. This happens in several cases, and is handled as described in the Fire and Assaults sections below.

Reading Combat Outcomes: The app will provide some information about the performance of units when they execute combat actions, in relation to the expectation of their performance, based on troop quality (an Elite unit is judged at a much higher standard than a Poor one!) For example, when a unit is being assaulted, and conducts a defensive fire, it's performance will be rated as "brilliant," "excellent," "strong," "moderate," "weak," or "very weak". Similar descriptions are given to units firing, and units conducting assaults. Note that these ratings do not guarantee any particular combat outcome - they simply describe now well the unit conducted itself (that can be understood as how well the player "rolled" if you want to think of it that way.) Even a good result can be negated by other factors, such as the opponent's "roll" or various modifiers, however.

French columns maneuver into position at the edge of a town - evicting them could be tough!

Fire actions include deployed fire and advancing fire. Deployed fire may only be made by units beginning their action for the turn in a deployed formation. Advancing fire may be made by units in a variety of formations. Deployed fire is significantly more effective than advancing fire, because more of the unit's battalions and batteries are in a position to fire (in linear formations and/or skirmishing or unlimbered), and will be positioned to have the best possible fields of fire, with ammunition supplies to hand. Units in March Column may never fire.

Cavalry units were not consistently armed with firearms in this period, and the cases where mounted regiments, much less brigades, used their firearms as a primary means of attack (as opposed to skirmishing) are vanishingly few. Consequently, cavalry brigades do not conduct fire in this game. Similarly, although transport guards would have been equipped with muskets or carbines, transport units are also not allowed to fire: there simply would not have been enough volume of fire to produce a meaningful effect at the scale of these rules. Only infantry and artillery units are allowed to conduct fire actions.

The formation of a target unit is also important for fire actions: when a unit is deployed, it is less vulnerable to fire. When a unit is in maneuver formation or square, it is more vulnerable to fire. A unit in march formation is the most vulnerable to fire.

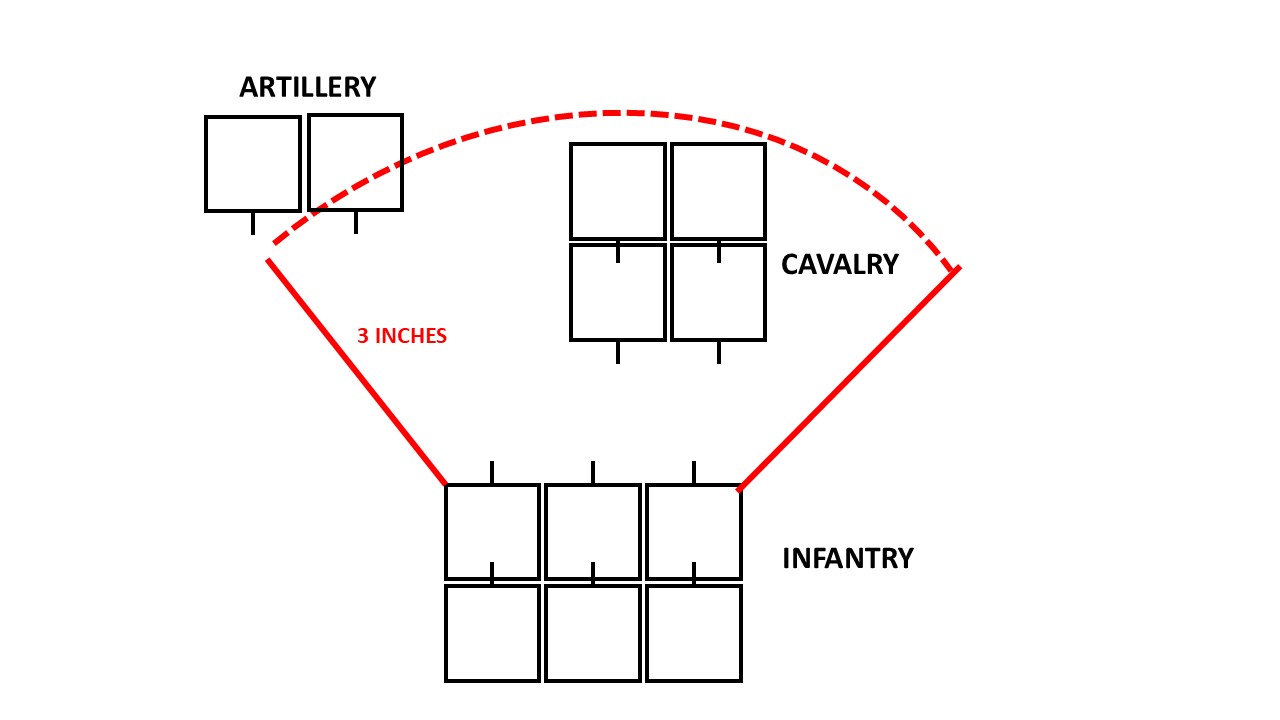

The targets of fire actions must be within the range of the firing unit (3 inches for infantry, 9 inches for light or horse artillery, and 12 inches for heavy foot artillery). Range and LOS are determined by measuring from any part of the front of the firing unit to any part of the target unit. The program interface will inform you if you attempt to fire at a target which is out of range. You are still considered to have made an action when you receive an out-of-range fire effect - the unit cannot make another action that turn. Targets of fire must be visible to the firing unit, and they must be within arc of fire. Visibility is determined by a clear line of sight (LOS). Some terrain will block LOS, and some terrain will permit fire over the heads of friendly units under certain conditions (see Terrain, below). Visibility into and through woods (and similar terrain) penetrates only 3 inches, limiting fire within woods to this range. Targets of fire must be at least partly within an arc of fire going forward and outward 45 degrees from each of the front corners of the firing unit, as shown in the diagram below:

In the diagram, we have a maneuvering infantry unit conducting an advancing fire. It has two possible targets, a cavalry unit which is clearly within both LOS and arc of fire, and an artillery unit which is only partially within arc and LOS. Both are valid targets, and the infantry may choose which one they are planning on targeting with their fire. (It helps to remember that the units are actually groups of battalions, which may be in different parts of the area occupied by the brigade, and that much of the firepower may be coming from skirmishing units ranging out ahead of the main body. Given the time scale in this game, it is notionally possible for these sub units to move so as to better target the enemy, although this is not reflected on the tabletop by moving the figures.)

You are not permitted to fire along a line-of-sight which goes through or closer than half an inch to friendly troops, unless you are firing over their heads (see Terrain, below).

Note that assaults also involve fire combat, but this is computed by the program as part of the assault. It does not require any separate action on the part of players.

Whenever the firing unit has more or fewer bases than the target unit, then the Outnumbered boxes must be used. Check the "Actor Outnumbered" box if there are more bases in the target unit than in the firing unit by at least a ratio of 3:4, but not twice as many. Check the "Actor Badly Outnumbered" box if there are twice as many or more. Check the "Target Outnumbered" boxes if there are more bases in the firing unit than in the target unit, using the same ratios. If the firer and target are equal in number of bases, check the "Forces Even" box. Firing units will always count all of the bases in their unit, regardless of how many have a clear LOS or firing arc on the target. Targeted units will always count all of their bases. Every unit fires separately, so numeric odds are calculated separately for each unit.

The effects of fire are described in the sections above.

A horde of French attack, including some of their German allies from Wuerzburg! (Their uniforms and flags look like Austrian ones, but they're not...)

Infantry and cavalry units starting their action in Maneuver Column formation may make assault actions. This represents the close-range fire and hand-to-hand combat which occurred frequently when units were ordered to take a position. Attackers would advance, generally without firing (they would tend to stop moving forward), subject to the fire of the defenders. If they could stand the defensive fire, melee often followed, and was often successful even against entrenched defenders. The biggest danger to an assaulting unit is the defensive fire which is made by a defender. This can be mitigated by choosing a target unit which is disordered and by not making a frontal assault (that is, an assault through the target's arc of fire). Even so, assaults can be dangerous - assaulted units may refuse a flank, and even disordered units can sometimes be successful shooting at close range. Best is to assault a unit which is demoralized - demoralized units will fight but do not organize coherent defensive fire against a charging opponent. Targets in March Column formation are also a good choice. Cavalry in the open has no strong defensive firepower but excels at close combat.

When making an assault, there must be a clear LOS to the target unit and it must be brought at least partially within the firing arc of the assaulting unit with an initial wheel. The target of an assault must be within 6 inches (base movement) for assaulting infantry units and 12 inches (base movement) for assaulting cavalry units. These distances are modified by terrain just as movement is, made along a straight path between the center front of the assaulting unit and the nearest part of the target unit (the "assault path"). The target unit must be within the modified distance. For assaults where orders are delayed, the same process is used but the distance is reduced, as indicated by the program interface. A frontal assault is any assault which crosses the firing arc of the target unit, as determined by the assault path between the two units.

Assaults may sometimes fail to "go home" - that is, the assaulting unit may be stopped by fire before making contact with the target unit. Any assault in which the assaulting unit is forced back to its starting position, or stopped 1 inch from the target unit, is a charge which has not "gone home." In this case, the assaulting unit will have used its action for the turn, but the target unit - if it has not already acted for the turn - may still make an action. If a charge goes home - that is, defensive fire does not stop the assaulting unit 1 inch away, or push it back to its starting position - then both the assaulting and target units have used their actions for the turn (they are occupied by the close combat and its aftermath). In this case, the assaulting unit is moved along the assault path into contact with the target unit of the assault, before any combat effects take place (which might push the target unit back). Note that in cases where the assault goes home but is defeated in close combat, the assaulting unit may not actually need to be moved (eg, it moved forward 6 inches into contact and was pushed back 6 inches). Notionally it still moves, however.

The Outnumbered check boxes are used slightly differently in assaults than they are for fire. In an assault, the target is outnumbered if the total number of bases of all units which have assaulted the target that turn, at the time they made the assault, are greater than the number of bases in the target unit. To give an example: I have a French infantry unit of four bases which is assaulted by a Prussian infantry unit of four bases. Neither actor nor target is outnumbered for this action - both have four bases. If there is another assault during the turn on the same target unit, all four of the bases from the first assault are counted (even if the first assaulting unit lost bases as a combat result) when calculating outnumbering for the second assault. Thus, a second assault made by a three-base Prussian Infantry unit would outnumber the four-base French unit, because it adds the number of bases of the first assault (4) to its own number of bases (3) to get 7, which outnumbers the target unit's 4 bases. A third assault would add all 7 of the bases from the preceding assaults to its own total. This represents the mounting fatigue, stress, and expenditure of ammunition as multiple assaults are repelled.

Unlike fire, the combat effects of assaults may affect either or both of the participants. These effects are described in the preceding sections.

Linear Tactics: While the typical Napoleonic assault formation would be columns preceded by a cloud of skirmishers, some armies were trained in more "traditional" fashion, These would include the British (although arguably not by the time of Waterloo), the Austrians (at least until the 1809 campaign), early Russians, early Prussians, and so on. Units from these armies are allowed to make assaults in Deployed formation, although the range of those assaults is limited to 2 inches. In some of these armies (early Prussians especially) assaults in a Maneuver Column formation - that is, in column - should be dis-allowed. Players should agree on such tactical niceties, or they should be established by scenario, as there are many different opinions about how the different armies fought at different points during the period.

Note that cavalry will not be allowed to make assault in Deployed formation: the Maneuver Column formation represents a series of lines, one after another, in close order. For cavalry, a Deployed formation is being spread out to avoid taking heavy casualties (typically from artillery fire) and would not be used to make an assault.

Artillery Support: It is possible for infantry to units to act as supports for artillery units. This is achieved by having them share a facing, and being in contact along either side of the units respective formations. This represents artillery being tactically integrated with an infantry formation. When an undisordered infantry support is in contact with an artillery unit, the artillery cannot be targeted for assaults - the infantry unit must be attacked instead. Note that infantry in March Column formation cannot act as supports for artillery - any other formation can.

Countercharges: Cavalry being frontally assaulted by cavalry in the open ,ay choose to move forward to meet the assaulting cavalry halfway between the two units, to reflect te fact that cavalry would generally countercharge if possible. This is not allowed for breakthrough charges however (see below), or if the target unit is Disordered or Demoralized.

Breakthrough Charges: If a cavalry unit makes an assault and the enemy is forced back or removed from play, the cavalry may continue forward with whatever movement they have left and - if they contact an enemy unit - they may assault it in the same turn. The target of such a "breakthrough charge" must be within the frontal arc of the cavalry unit (45 degrees to either side of facing and must be within LOS of the cavalry unit at the point where it starts the breakthrough charge. It is not permitted to make two breakthrough charges in a single turn, however.

Terrain can have a huge effect on play, influencing movement and providing cover or advantageous ground in an assault. Terrain may also permit or stop potential fire and assault actions by blocking the line of sight (LOS). Scenarios should specify the characteristics of all tabletop terrain before play begins.

Movement: There are several types of terrain from a movement perspective: open terrain, rough terrain, impassable terrain, roads, linear obstacles, and choke-points. Open terrain is typically fields - ground which does not impede movement. Rough terrain can be woods, swamps/marshland, rocky hills, or similar types of features. It slows movement by half for infantry and artillery and by three-quarters for cavalry and generals. Impassable terrain cannot be entered or crossed - it consists of such things as cliffs, deep swamps, and unfordable rivers.

Roads are "improved" roads (that is, metalled ones - typically gravel packed over larger sub-stones) and not just dirt tracks. They speed the movement of marching units by half. Linear obstacles are walls, hedges, and other obstacles that must sometimes be crossed. They will cost a penalty of a half inch off of base movement for units which cross them (note that, while individual mounted horsemen can easily jump some linear obstacles, entire cavalry brigades generally cannot!) Choke points are bridges, gates through otherwise impassable walls, and similar points where movement is constricted. These cost a half inch of base movement to pass, unless the unit is marching. Note that many such choke-points are also roads (bridges, for example). Towns are a special category of terrain. For units marching, they act as roads. For other formations and types of movement, they count as rough.

Cover: Terrain can also provide cover for fire and combat purposes. Open terrain does not provide cover, nor does the type of rough terrain (such as swampy ground) where there is not much above ground level to provide protection from prying eyes or bullets. Fords across rivers are an excellent example - they impede movement, but do not conceal or protect those crossing them. Some terrain will provide a slight or significant advantage to defenders in a combat situation. Steep slopes, river banks, and similar may not provide cover from fire nut may count as "soft" (slight advantage) or "hard" (significant advantage) cover for the defenders against assaults.

Soft cover is that type of cover which serves to conceal troops - the typical example is woods. Other types of cover also act as soft cover: villages may consist of structures made of softer materials which will not stop bullets (wooden barns/houses/sheds); and many types of hedges and fences will conceal but not provide the degree of cover which will stop a bullet or shell.

Hard cover includes stone walls, the solid buildings of stone or brick found in towns, and naturally protective "soft" areas which have been fortified (fortified villages, for example). It also includes prepared trenches. Fortifications include redoubts and fortresses - places where engineers have designed and built military fortifications.

In cases where a target unit is only partly inside protective terrain, modifiers should be used based on where the attack is impacting the target unit. If the part of the unit being targeted is protected, then the appropriate modifiers should be used. If the part of the unit targeted is even partly unprotected, they should not benefit from the terrain advantage.

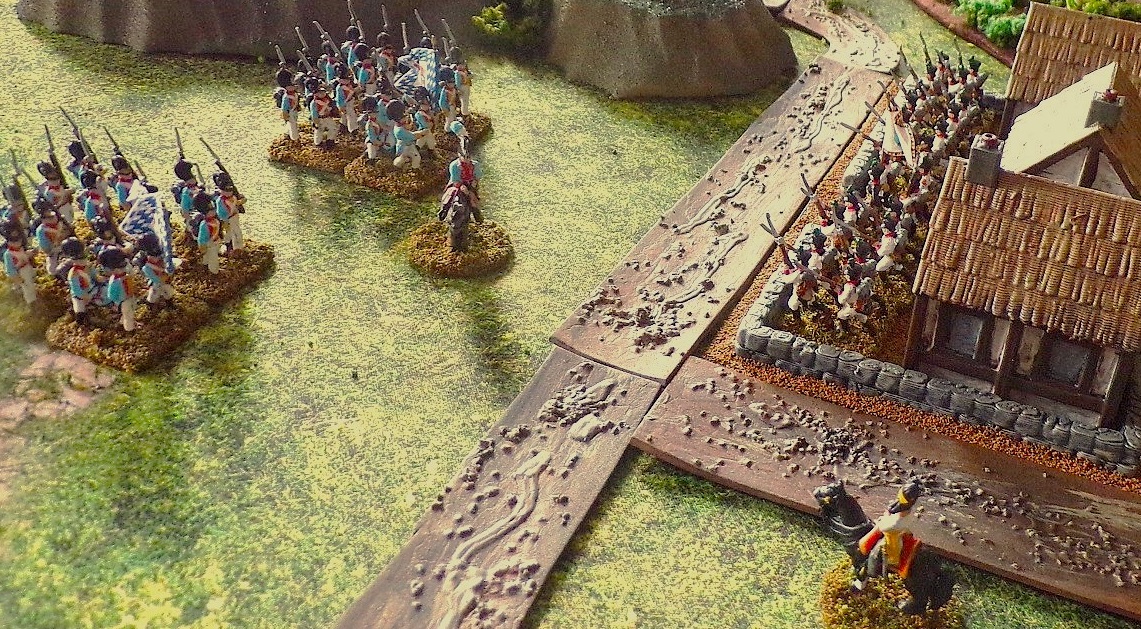

Bavarians approach a unit of Austrians defending a town during a refight from the 1809 campaign on the Danube.

Line of Sight (LOS): Terrain also acts to obstruct line-of-sight. To determine LOS, a line must be drawn from any point on a base of the spotting unit to any point on a base of the unit being spotted. Ranges for fire in this game are calculated as the shortest clear LOS between the firing unit and its target (round down if they are on a break-point measurement such as 3, 6, or 9 inches). If the potential LOS crosses any terrain, it may be blocked. There are rules for determining what can and cannot be seen.

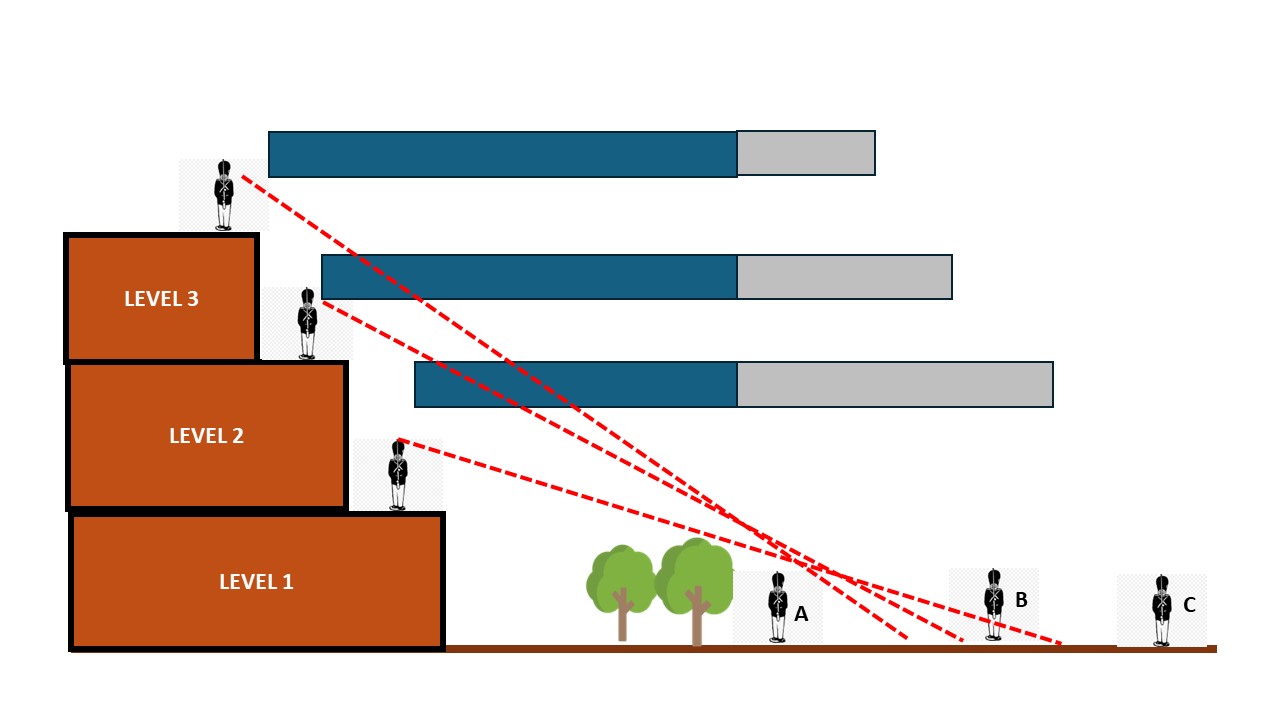

For this purpose, terrain is classed according to a series of levels: ground level, low obstructions (hedges, walls, wheatfields, etc.), taller obstructions (houses, woods), low hills, taller hills, even taller hills (etc.) - each level of hill is a "terrain level." Terrain in all of these different height categories may be found on the tabletop. The rule for LOS is that if you can see them, they can see you - it works in both directions. Low obstructions may provide soft or hard cover to troops immediately behind them, but do not block LOS. Taller obstructions such as houses and woods will block line of sight across the same terrain level, but may not block LOS from higher levels, according to a more complicated system: at one terrain level up, your LOS will not be blocked if tall obstructions are closer to you than they are to the target. For each terrain level you go up, half of the area blocked from the level below becomes visible. See the following diagram:

For aesthetic reasons, our figures and terrain pieces are not in agreement with the ground scale. Thus, what we see on the table is not how it really is. This system gives you a way of approximating reality. (Short of going and surveying critical vistas on the battlefield, or having a really good 3-D model, you won't get better than an approximation. There are wargamers who have visited and surveyed important battlefields, but from a practical perspective this is not an option for most of us.) In the diagram, we have hills on the table up to 3 terrain levels tall. We also have a tall obstruction (woods).

If we have a unit on the first terrain level trying to spot a unit beyond a tall obstruction on the ground level we calculate the "shadow" cast by the tall obstruction as follows: Measure the distance from the spotter to the far side of the tall obstruction (the blue bar by the first level figure). Anything beyond the tall obstruction for an equal distance (the grey bar) or less is hidden. Thus, target figures A and B are hidden, but target figure C is visible.

When you go up one level, the same thinking applies but the length of the shadow is reduced by half. Thus, we can tell that target figure C is still visible, target figure B has become visible, but target figure A is still hidden by the shadow of the tall obstruction. When we go to the third level, the shadow is reduced by half again (so now it is only 1/4 of the distance between the spotter and the far side of the tall obstruction). Figure A remains hidden, but the others are clearly visible.

If you have more than one tall obstruction between you and the target you want to spot from above, and the obstructions are on the same terrain level below you, always check the one closest to the target. If that one isn't a problem, none of the others will be. Note that model hills for wargames are often stepped, to allow figures to stand on them at different levels. Often, these are meant to represent sloping hills rather than a series of stepped plateaus. The scenario should specify the nature of hills, so they are interpreted correctly during play.

The same system is applied to firing over the heads of friendly units. Treat the friendly units as a tall obstruction: if the target would be visible (according to LOS rules) then you are allowed to fire on it.

This is a little complicated, but it is important to any simulation of Napoleonic warfare. Terrain makes a huge difference on the outcome of battles, and LOS is a big part of that. Although this system may seem a little complicated at first, it is really based on common sense. Once you get used to it, it starts to become obvious.

Generals have few functions in this game, but they can be important. The first is to help guarantee that orders are received and obeyed without delay. They do this by being within 6 inches of the unit being given the order. This does not apply to fire orders - the brigade commanders would know to fire on the enemy troops without orders from above. The second function of generals is to help regroup disordered and demoralized units. Again, they do this by being within 6 inches of the unit which is regrouping.

Generals cannot make any combat actions, nor may they be the target of combat actions. Their only actions are to move and to rest. They influence their troops via their proximity. Note that generals will influence any number of units during the turn, within which they are in proximity, and that they may move during the turn to bring new units into range of their influence. They may only move once during the turn, however, and they cannot stop to use their command influence during movement and then continue moving.

Generals which are "run over" by enemy movement will need to check to see if they are killed or captured. Click the "Leader Overrun" button and answer the questions it asks, and then remove the Leader from play if killed or captured, or move the general away as instructed. (This may seem like an odd mechanic, but Napoleon was known to specifically target the HQ of his enemies during battles, hence its inclusion here.) Leader who are killed or captured are not replaced - it is assumed they are replaced by subordinates with less command capacity who do not have the ability to control units like the generals they are replacing.

During the game, if at any point an army has a full half of its units broken and removed from play, or in a Demoralized state, then there is a chance the army will break. The "Army Morale" button must be clicked and the questions answered - the app will determine whether the army will continue fighting. This check is performed only once per turn, as soon as the half-way mark is reached. If the army passes, and continues to fight, on subsequent turns if a unit in that army is destroyed or demoralized, another check must be made. If enough units have regrouped, such that a full half of the army is no longer broken or Demoralized, no check is needed - the army must ne at the halfway point or worse for a check to be made.

The effects of a failure of army morale are immediate - the game ends!

There are many different rules systems available for the Napoleonic period, covering a huge range of styles of game at different tactical levels and differing levels of detail. There Stand Empires is different in part because it employs a game app where others use paper-and-dice mechanisms, but this difference alone does not radically change the style of play, or the game as experienced by players, aside from that fact that it no longer involves the rolling of dice. It is worth describing the design goals of the system, so that players and potential players can understand what is intended.

The use of dice in games as a mechanism for random number generation is a topic which could be discussed at length on its own: suffice it to say, dice of different types can be employed well or badly from the perspective of probabilities and outcomes, and this is often driven by how dice modifiers are assigned, and where different rolls are employed in the game sequence. In many - and perhaps the majority of - cases, the use of dice acts to badly distort the intended probabilities of a game designer, based on the idea that a proliferation of modifiers produces an increased level of realism in games. Especially in the modern crop of fast-play games, it seems like game designers never consider the mathematical effect of modifiers (and re-rolls, especially) on the statistical probabilities of outcomes, even though the net effect may be to remove any hope of simulation from the game. For many "fast-play" systems this seems to be acceptable to players: they want to have fun rolling dice, and don't really care whether what happens on the tabletop is particularly realistic. They are engaged in a history-based fantasy, not an historical wargame. Other games place more importance on realism, but still run afoul of the idea that the use of lots of dice modifiers makes a game more realistic, where it also has the countervailing effect of potentially introducing very high levels of distortion. Using a computerized app to determine outcomes does away with all such questions: the algorithms used are exactly as written, without the distorting influence of dice. Players may enjoy rolling dice, but that is not what this game is for!

Instead, it is hoped that a "fast-play" gaming experience can be gained without sacrificing too much realism. The game app allows us to perform more complex calculations more easily, without requiring players to do math or work through elaborate sequences of actions for particular tabletop events, accompanied by look-ups in reference material or charts. This game attempts to enable players to complete large grand-tactical battles from the perspective of a Napoleonic corps- or army-level commander without sacrificing too much realism. Yes, many lower-level battlefield functions are abstracted, based on calculations performed inside the app, but because the burden of performing each operation step-by-step has been removed, this can support a greater level of detail than other fast-play Napoleonic systems using paper-and-dice. (That said, it is probably less realistic than other computer-based systems which track more information about each unit, such as the popular Carnage & Glory.)

As a designer, I believe that many Napoleonic systems suffer from too heavy an emphasis on details about which we do not know enough to model them into our games realistically. Generalizations about nationality-based performance are typical of this: Austrians always behave one way, while Frenchmen do another, and Russians a different way yet again. (And don't get me started on the British, who seem sometimes to be supermen for no better reason than the mythologizing of Waterloo by rules writers.) I feel like the demand from the wargaming community that unknowable aspects of the period be reflected in game systems, to add "period feel", has in many cases been taken too much to heart. Generals and units are given "special powers" when this is not justified by the historical record, or reflected in any plausible way in the game system. Flavor, perhaps, but of what? Not history, in any event.

My answer to this is to downplay the supposedly realistic mass of detail in favor of what the generals commanding corps and armies in the period probably believed: that a soldier was a solider and they could be expected to do their duty, according to their training. If we as players are to take the roles of the generals, and be given the ability to change events on the battlefield, shouldn't our decisions, rather than some historical characterization of national or unit performance determine the outcomes? Yes, there are significant differences in troop quality, and generals knew which of their units were more reliable than others, but did they actually think about their armies the way modern wargamers think about theirs? I sincerely doubt it. This game takes a minimalist approach to these issues, reflecting the basic differences between troop types and functions, and the levels of quality, but does not presume to know every detail of every general or every nationality-based predeliction of each class of unit. (Although a longtime fan of Napoleon's Battles, that system attempts the impossible along these lines, and I have always found it bemusing.)

As a computer-assisted system, I wanted to produce a game where the computer - while not perhaps utilized as fully as in other game systems for record-keeping and so on - could be employed in a less-intrusive, minimalist fashion. By reducing what is a set of screens in other computer-assisted systems to a single one which can be run on a number of devices at the same time, it attempts to solve some of the usability problems which face this type of game. I first attempted this in the La Guerre à Outrance system for the Imperial phase of the Franco-Prussian War, and have further refined it here to cover a much broader conflict. The game app allows what would be a very heavy load of chart look-ups and dice rolling to be reduced to the click of a button, while not usurping the function of the tabletop itself as a way of keeping track of the battle. In this way, it avoids some of the difficulties faced by computer-assisted systems which handle more of the game mechanics inside the machine, but are prone to dis-connects between what is going on inside the computer program, and what is visible on the table. Ultimately, it allows for a "chess-problem" approach to historical miniatures: a game which by definition must play suitably fast. The same level of detail would not have been easily possible with a paper-and-dice fast-play system, even though that may be what the gamer sees on the table.

I hope gamers enjoy There Stand Empires in the intended spirit!

Arofan Gregory, May 2025